How to Read the Old Testament - Part 2 - Michael Brown

Last year I was given a new novel for Christmas and at first, I was excited. The cover of the book was colourful and striking and the title was intriguingly cryptic, ‘Simply Jamie’. I couldn’t wait to dive into this new story and find out the answers to these mysteries; who was this Jamie and what made him so simple? But I was disappointed.

The book seemed to have been written in an experimental, unorthodox style which made the plot extremely difficult to follow and character development basically non-existent. The chapters were extremely short and disjointed and the prose also left much to be desired with the author making far too much use of words like ‘pukka’ and ‘gnarly’.

I mean here’s an example of a standard page so you can see what I mean:

As you can see it’s not exactly Hemingway. In the end I sadly had to give up on the adventures of simple Jamie.

"Expectations of genre are incredibly important to how we read and understand a text."

Now clearly, I’m being facetious. I know full well that this is not a novel but a recipe book and I mean no insult to the fine culinary works of Jamie Oliver, of which I own several (other recipe books are available). The point I am making with this example is that our expectations of genre are incredibly important to how we read and understand a text. We don’t read novels in the same way that we read recipe books, or dictionaries in the same way as poetry collections.

So, the genre expectations that we bring with us when we read a book have a huge effect on the understanding that we take away from it.

Except with the Bible, we have the added complexity that we are dealing with a very ancient text, from a far-removed culture with very different forms of literature to the ones we know. I know what a modern history book looks like and how they are written. I know how modern poetry functions. I am familiar with the tropes and genre conventions of 21st century comic books. What I am not so familiar with are the genre expectations and writing conventions of Israelites living in the 1st and 2nd millennia BC.

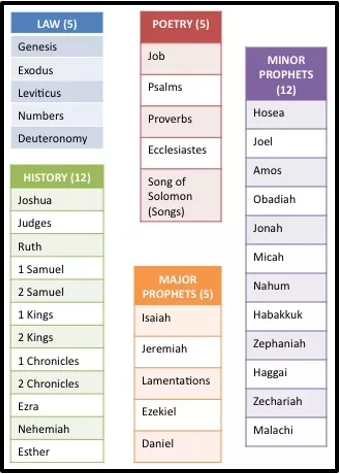

So let’s take a look at what genres we find within the Old Testament:

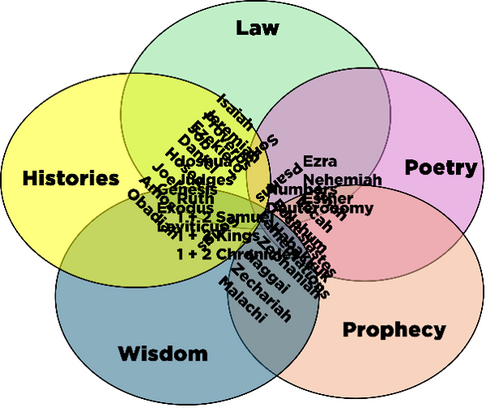

These are the classic genre divisions that we find within the Christian Bible; the 5 books of the law, the histories, the poetry (sometimes called the writings) and the prophets (both major and minor). However, if you have read many of these books you will know that these divisions do not even nearly tell the whole story.

For starters, the five books of the law do not only contain lists of laws but are actually largely narratives. There are large prophetic sections all over the place in the histories and poetry. A more accurate diagram for the genres of the Old Testament would look like this:

In reality, the books of the Old Testament just don’t fit into the neat categories of our modern genres. Take the histories for example. When we see that word ‘history’ attached to a book our first instinct is to then read those books with all the expectations that would come from what we understand a history book to be.

The problem with that is that these books are not written in the same way and with the same purpose as a modern history book. In fact, at the time these books were written the genre of history books had yet to be invented. That would come with a guy called Herodotus in the 5th century BC.

Our history books are written with a primary purpose of transmitting information as accurately as possible and in as much detail as possible. Names, dates, locations and order are all of utmost importance and the aim of the author is primarily to give you as good an understanding as possible of what happened. But that is not how the Old Testament books work.

"These are books that have been written to teach you about God, to teach you about who he is and how he interacts with the world, and we ought to interact with him."

The primary purpose of the so called ‘histories’ is a theological one. These are books that have been written to teach you about God, to teach you about who he is and how he interacts with the world, and we ought to interact with him. That is the main intent of the authors of these books and everything else is secondary.

Now this isn’t to say that the stories are just made up, that they are therefore not historical. No, it’s clear that the authors were recounting the remembered history of their people, events that they clearly believed actually happened. But whilst doing so they were retelling these stories in such a way as to teach the reader things about God.

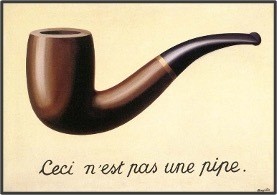

A good illustration of this is this famous painting but the artist Rene Magritte:

The sentence underneath the picture reads “this is not a pipe”. Magritte is making the point that depiction of an object is different from the object itself. This is a painting of a pipe, not a pipe. It has authorial intent, the artist has chosen what type of pipe to paint, what colour to use, what lighting to depict, what angle it is displayed at.

The books of the Old Testament are much the same, the authors are taking the stories of their people and telling them with authorial intent. They are deciding which stories to include, which characters to focus on, what details to tell and what to leave out and most importantly what lessons the reader is supposed to take away with them.

"They are depictions of history; they are not history."

They are depictions of history; they are not history. They are theological, historical narratives with the historical purpose being primary over the historical and there are countless examples where we can see the primary focus of teaching the reader about God taking precedence over the need for historical accuracy in the details.

Let’s look at some examples.

In 1 Samuel 11, just after Saul has been anointed as King we read the following:

1 Nahash the Ammonite went up and besieged Jabesh Gilead. And all the men of Jabesh said to him, “Make a treaty with us, and we will be subject to you.” 2 But Nahash the Ammonite replied, “I will make a treaty with you only on the condition that I gouge out the right eye of every one of you and so bring disgrace on all Israel.”

1 Nahash the Ammonite went up and besieged Jabesh Gilead. And all the men of Jabesh said to him, “Make a treaty with us, and we will be subject to you.” 2 But Nahash the Ammonite replied, “I will make a treaty with you only on the condition that I gouge out the right eye of every one of you and so bring disgrace on all Israel.”

Now to a modern English reader this might seem unremarkable, it’s just telling us the name of the Ammonite leader. But to an ancient Israelite something would immediately jump out to them. You see Nahash is a Hebrew word and not an Ammonite one. Not only that but it is a significant Hebrew word, it means ‘snake’ or ‘serpent’. The author here has given this name to the Ammonite king in order to make a theological point.

Saul has just been anointed a God’s chosen king, his holy one or mashiach, and now he is going up against a snaky bad guy. This is part of a long running theme, that goes throughout the Old Testament, depicting God’s anointed servants battling against evil doers who depicted using snake imagery and language.

The same will happen with David and Goliath (Goliath’s armour is described as being scaled bronze, bronze being spelled with the same letters as Nahash (snake)). It’s the ‘seed of the woman’ battling the ’seed of the snake’ (Genesis 3).

"What is more important for us the reader, that we know the real name of this Ammonite king, or that we gain a greater understanding of God’s plan for his people and for the defeat of evil?"

The alternative would be to say that this man’s name is rather randomly, and improbably, the Hebrew word for snake. So here we have a prime example of how historical accuracy is a secondary concern to the theological truth behind the story. And after all what is more important for us the reader, that we know the real name of this Ammonite king, or that we gain a greater understanding of God’s plan for his people and for the defeat of evil?

This is just one example and just one genre, there is plenty more that we could say about how the Bible treats history, without even getting to how poetry and prophetic literature works. But I hope this has been helpful in illustrating a little bit of how we need to read the Bible on its own terms, without reading our modern genre conventions into the text.

Next time we will be looking at some of the other barriers to our understanding of the Old Testament, namely culture, context and language.

Read the other blogs in this series here:

How to Read the Old Testament - Part 5 - Michael Brown

February 9th, 2026

How To Read the Old Testament - Part 4 - Michael Brown

January 29th, 2026

How To Read the Old Testament - Part 3 - Michael Brown

January 22nd, 2026

How to Read the Old Testament - Part 2 - Michael Brown

January 15th, 2026

How to Read the Old Testament - Part 1 - Michael Brown

January 9th, 2026

Recent

How to Read the Old Testament - Part 5 - Michael Brown

February 9th, 2026

How To Read the Old Testament - Part 4 - Michael Brown

January 29th, 2026

How To Read the Old Testament - Part 3 - Michael Brown

January 22nd, 2026

How to Read the Old Testament - Part 2 - Michael Brown

January 15th, 2026

How to Read the Old Testament - Part 1 - Michael Brown

January 9th, 2026